Experts identified the Coronavirus in China in December 2019, and the first serious evidence to the massive impact of COVID 19 spreading in Japan began in March 2020. Reports started with alerts that there were 15 clusters throughout the country, with the most significant group, accounting for more than 80 cases, involving four live music venues in Osaka. Authorities identified another ‘live house’ in Sapporo as a cluster. At the same time, Nagoya city officials said a group tied to a sports gym was on the decline. However, they were struggling to handle another expanding cluster related to an elderly day-care home.

Experts identified the Coronavirus in China in December 2019, and the first serious evidence to the massive impact of COVID 19 spreading in Japan began in March 2020. Reports started with alerts that there were 15 clusters throughout the country, with the most significant group, accounting for more than 80 cases, involving four live music venues in Osaka. Authorities identified another ‘live house’ in Sapporo as a cluster. At the same time, Nagoya city officials said a group tied to a sports gym was on the decline. However, they were struggling to handle another expanding cluster related to an elderly day-care home.

The OECD reported local authorities and public transport companies throughout Japan were quick to advise on measures to halt the spread of the virus. Although there was fear that subways, trains and buses would be a massive problem with clusters developing as people commuted, there was an absence of detected clusters on public transit as passengers seem to be paying attention to safety guidelines. Commuters in Tokyo have long been wearing masks though the flu season, a habit long ingrained in Japan, and was maintaining as much social distance as possible. Observers of Japan’s low transmission rate for public transit have also noted that public transport users tend to travel in silence; significant since speaking is a very effective disperser of virus-infected aerosol.

Schools throughout Japan, managed by the prefectures at senior high school level and the municipalities at junior high and elementary school level, were asked to close by Prime Minister Abe at the end of February 2020 with the government alarmed by the spread of the virus where health authorities identified outside China than inside its borders. With long term closure becoming a reality after initially thinking schools would only be closed until the new academic year in Japan starting in April, Japanese local authorities had to swing into action to support some 13 million students throughout the country.

There was the support given to students in Yokohama through lessons being made available to watch on the subchannel of the local television station TV Kanagawa from 20 April, recognising there might be students who cannot access the internet. Both the City of Yokohama and Kanagawa Prefecture are significant shareholders of the channel, along with other private sector media companies. Similar measures were taken in other parts of Japan, such as rescheduling semesters, postponing examinations and upscaling the provision of online learning tools and educational applications free of charge. Fukuoka Prefecture provided online content with educational films for children who stayed at home due to the closure of public schools there.

Japanese local authorities have a vital role in supporting the local economy and identified the need to support local businesses swiftly. Tokyo Metropolitan Government developed a recovery roadmap, including guidelines for firms to prevent the spread of viruses accompanied by subsidies for small and medium-sized firms to invest in appropriate facilities and equipment. In parallel, and to support the hotel industry, it set up a programme matching hotels providing teleworking facilities with employees who cannot telework at home, including a subsidy program to enhance wheelchair accessibility.

At the municipal level in the greater Tokyo area, businesses got the opportunity to change their operations to enable SMEs to adapt their business model. They were now allowing bars and restaurants to sell ‘off-licence’, with a streamlined licensing system for change of use of premises, reducing applications from 30 pages to one page in the case of some bars and izakayas in Tachikawa City in the west of Tokyo Metropolis, allowing off-site sales to sell beer for takeaway, giving a lifeline to the burgeoning local craft beer industry.

Measures were needed to maintain public safety, while at the same time supporting local business to continue to operate amid public health measures restricting regular business operation. This lead to the trialing of a new style of restaurants and bars using available pedestrian space in Saga prefecture (Kyushu island, west Japan). The programme called “SAGA Night Terrace Challenge” piloted in a central business district, a collaboration of Saga City and local business association, to provide safer spaces for customers to eat and drink, as well as supporting the local businesses and the night-time economy. Yokohama City created a website “Takeout and Delivery Yokohama”, to introduce and help restaurants offering set meal takeaways or deliveries. The city asked owners to register their restaurants so that residents can search their neighbourhood on a map.

Yokohama, like many other local authorities, also increased subsidies to the owners of rental apartments for vulnerable residents, so that they can reduce rent for tenants whose income was severely impacted by the pandemic. Similarly, prefectures and municipalities throughout Japan offered a range of subsidies for business and private individuals suffering a loss of income with social restrictions in offices and factories.

In addition to promoting telework or remote working, among its staff, Tokyo Metropolitan Government encouraged private companies to introduce flexible working hours. It took specific measures to support SMEs and other companies in this shift by providing subsidies for the introduction of necessary equipment and software required for ‘teleworking’, which was a slogan gaining popularity before the advent of the virus in the run-up to the planned date of the 2020 Olympics.

Crisis management is a well-recognised feature of Japanese local government, already well versed in planning for potential disasters with large scale earthquakes and tsunami an ongoing challenge, as well as torrential rain and widespread mudslides in recent years. While COVID 19 presents new challenges, the advent of the pandemic means prefectures’ and municipalities’ disaster management plans already reviewed regularly will now include pandemics.

The Asahi Shinbun newspaper reported that a research request to local government bodies had shown 90 percent of responding local authorities have already made provision for COVID 19 initiatives as part of their general planning for disasters such as earthquakes and typhoons. While natural disasters are sadly a standard part of policy planning in Japan, this necessitates planning for public health challenges as a regular feature of life in Japan’s public sector.

References:

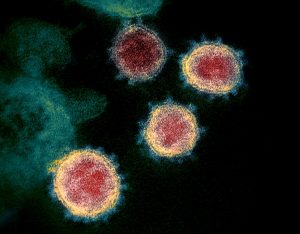

Image by NIAID – https://www.flickr.com/photos/niaid/49534865371/, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=92612457